Flip-Flopping with Ginger in the Smokies

MST. Chapter 44.

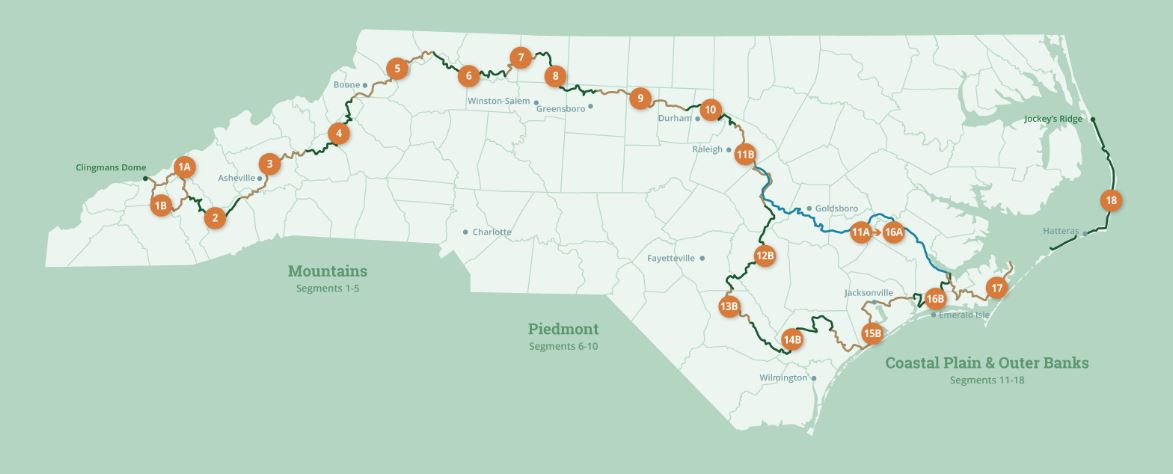

This is my serialized story of hiking the Mountains-to-Sea Trail (MST), a 1,175-mile route that crosses the state of North Carolina. I’m hiking west from Jockey’s Ridge near Nags Head on the Outer Banks of the Atlantic Ocean to Kuwohi (formerly Clingmans Dome) on the Tennessee border in the Great Smoky Mountains. If you’d like to start at the beginning of my story, click here.

See the Mountains-to-Sea map at the bottom for reference.

I am totally healed from my left knee “problem,” even though everyone says I’m still limping. As much as I try to disguise it, I decide a subtle limp is every bit as good as one healed and isn’t, unto itself, a significant reason to stop a four-day hike in the Smoky Mountains, especially in light of my dwindling window of opportunity—what with radiation and hormone therapy treatments planned by my relentless oncologists for later this fall. Bring on the Mountains-to-Sea Trail—I am now in my third year and still have four segments to go—a total of 259 miles to finish the 1,175-mile/eighteen- segment hike. My objective this summer is to complete these final four segments before all medical hell descends on me at the Duke University Cancer Center.

I say that, recognizing I am already compromised in completing the trail due to 71 miles of Segment Three and seven miles of Segment Four being closed to thru-hikers as a result of the devastation brought on by Hurricane Helene last September. Still, in light of the closures, I can complete a combined 180 miles of Segments One and Two, as well as 91% of Segment Four, if I flip-flop the route by heading east instead of west. This is an awkward shift in direction to my story, but due to expediency, I will get done what I can, leaving Segment Three and that last bit of Four for a future date—either when the U.S. Forest Service, MST volunteers, and the National Park Service reopen the trail or when I am medically (mentally?) capable of hiking again.

In truth, my disappearing window is already too short. So, I give my knee three weeks to be limp-free. Three weeks—but either way, I’m out of here.

I am thrilled to say that Ginger, my friend from the gym who has hiked with me previously, has agreed to join me for the four-day/three-night adventure and has even scheduled a week off from her job. After hundreds of miles of me hiking alone, she will be a nice presence on the trail and a stalwart companion—though, when she told me she hadn’t camped on a hike previously, I was a little concerned. Carrying a thirty-pound pack with a tent and sleeping bag, along with food, extra socks, and everything else, will be an experience I hope she will want to replicate (with me) in the future.

Three weeks, therefore, come hell or high water.

Before leaving, at the start of that final week, my wife Karen insists I go to our local orthopedic clinic to get my knee checked. The doctor confirms that it is likely a tiny medial meniscus tear that can’t be seen with x-rays. Most importantly, he says my knee shouldn’t be too impacted by my proposed hike as long as I wear the large, hard-core brace (with rubber rods on either side of the knee) that the clinic gives me. This, then, is the authorization I need to assuage my wife and the compromise I make for my tough segment hike to begin.

So, in late July, Ginger and I take off for Segment One, which starts at the top of Kuwohi (formerly Clingman’s Dome) in the Great Smoky Mountains near the Tennessee border with North Carolina. At 6,643 feet at the summit, Kuwohi is one of the tallest mountains on the East Coast. Our objective is to start here at the very, very beginning of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail and hike eastward (not westward as I have done in my ongoing narrative). For our first day we will hike down the mountain for nine miles to reach Deep Creek at 3,000 feet where we will camp for the night.

A nine-mile descent will surely test my knee once and for all.

I hope, too, Ginger won’t find the going to be too much. I remember my first time carrying such weight back in the Outer Banks when I started my walk on the MST and the painful shock to my shoulders, especially after the first several hours. Ginger and I don’t know each other all that well, but she mentioned she has a sore shoulder for which she sees a physical therapist. I hope she won’t hesitate to tell me when she needs to stop.

Ginger, though, is in great shape. She is in her mid-to-late fifties and, in addition to exercising on a daily basis, she has been day-hiking the Mountains-to-Sea Trail with a girlfriend for the past year or so. Together, they have nearly finished the three-hundred mile Piedmont section of the Trail. In fact, they are planning to kayak down the Neuse River to reach the eastern segments. She sees camping with me as a prelude to them camping along the river.

The first order of business is to drive three hours west on US I-40 and then one hour south down US I-74 (The Great Smoky Mountains Expressway) to meet up with my cousin, David. He and his wife, Kathy, live high on a mountain near Bryson City in Western North Carolina. David is an avid mountain biker who can’t understand why anyone would want to hike. Nonetheless, they will drive us to the top of Kuwohi.

David tells me when we meet that the entire area has been experiencing heavy rain in the afternoons and that we would be wise to carry umbrellas in addition to our backpacks. Perhaps, he says, attach the umbrellas to our heads, like beanies.

I’m thinking: Great. Rain along with a bum knee and Ginger who trusts that I know what I am doing. Just great. I haven’t hiked the MST since Hurricane Helene stopped me in my tracks just before starting Segment Four. It has taken nearly a year to reopen most of the western segments of the trail, and my subsequent diagnosis for prostate cancer shortly after the hurricane didn’t help. A radical prostatectomy in February, the months-long recovery from surgery—along with the realization that I will need to kill any lingering cancer cells this fall—and now the joy of fighting through four days of afternoon downpours—what a life.

Back in June, given my small hiking window, I doubled my effort to drop ten pounds and get into hiking shape. That was before I screwed-up my knee running in early July, which just underscored what a sucky year it’s been. Am I fooling myself in doing this hike so soon? Is Ginger a crutch to actually see if I still got “it” in spite of the cancer? Would I have done this hike without her? Worries that are no longer relevant.

Push to Deep Creek

After a quick lunch in the small town of Bryson City, David and Kathy drive us forty-five minutes up through the land owned by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, known as Qualla Boundary, past the town of Cherokee, itself, and into the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. They drop us off in the busy parking lot (with cars from dozens of different states) at the summit of Kuwohi and promise to pick us up four days later on top of the mountain known as Waterrock Knob.

We start our hike by shouldering our packs and walking with dozens of tourists to the Kuwohi Tower, a cement curlicue structure that provides a panoramic view of more than four states. As Ginger and I walk, I hear this cowbell-like ringing that seems to be coming from her pack. She says it’s a bell her daughter gave to her to ward off any bears we might encounter. I realize, the bell, rather than used on cows, sounds like the ring from an ice cream truck. I can’t help but wonder if bears won’t start following us—like mice shadowing the Pied Piper—slobbering for the sweet taste of creamsicles and Klondike Bars.

The cloudy weather, unfortunately, doesn’t hold for long and within minutes of walking with our oversized packs to the tower, the mid-afternoon rains arrive. Soon we are drenched in a sustained downpour complete with lightning and thunder.

In the rain we find our trailhead after patting the central kiosk of the Kuwohi Tower. Rain or shine, let the forty-six mile challenge of hiking Segment One begin. We immediately enter the forest and leave the scrambling tourists behind.

In planning our trip, I estimate that hiking the nine miles to the primitive campsite at Deep Creek will take only four hours, but as the rain pelts us and creates torrents of water on the slick, rocky, and root-entrenched trail, it becomes abundantly clear that I have miscalculated. Instead of hiking two miles-an-hour down the steep, forest-drooping slope, we are managing barely one. At this pace we won’t reach our campsite until long after dark—not a fun way to introduce someone to overnight backpacking, let alone begin a four-day/three-night hike.

The brace on my left knee is soaked and cumbersome but seems to keep my leg supported and stabilized on this wicked portion of the trail. Though it’s a pain to keep pulling it up over my knee in the rain, I am glad I have it. Finally I yank the brace so tight, it isn’t going anywhere. Blood circulation, though, be damned!

We follow white blazes on the trees, which makes identifying the trail a lot easier in the heavy rain. Then, I realize, these blazes are for the Appalachian Trail—we are sharing the climb down the mountain with the Appalachian Trail. I can’t help but wonder if I won’t be climbing up this trail one day hiking north on the AT from Georgia to Maine. I am sure I won’t forget how steep this section is.

The rain slows, then stops four miles into the walk. Soon we leave the AT following the signs for the MST as we navigate the final five miles continuing down the steep slope. Aware of our time, the late afternoon hike becomes more and more stressful. I am not sure Ginger is aware, but I pick up the pace to reach the campsite in daylight.

The trail, though, at times is obscured by wet, overgrown vegetation and, with just a small track cut out on the slanting slope, the footing becomes treacherous. On different occasions we both slip and fall on our butts and discover in so doing that with the heavy loads we are carrying, getting up requires unbuckling and picking up our packs separately. On top of that, at one point, I realize, in stopping a fall, I have applied so much pressure on my hiking poles that one of the metal sticks has bent a little at the bottom. Damn! I paid good money for these sticks too!

At another point, I fall backwards onto my thick pack and cannot move in the narrow track of the trail. This must be how turtles feel when they are on their backs. Ginger gets down on the ground beside me and opens my buckles so I can wiggle my arms free. As I crawl to safety, she holds my pack to keep it from tumbling down the steep slope. Such an awkward predicament takes more than ten minutes to untangle—time we can’t afford to lose.

Late into the evening, we reach the campsite next to Deep Creek. I am thrilled and very relieved, but I don’t allow us to stop and celebrate. We have just enough lingering light before the darkness of the wilderness descends on us. We quickly put up our tents and boil water for a shared rehydrated meal of Cuban Coconut Rice and Black Beans. Finally, over such a dinner, we can relax. The sound of rushing water splashing against the jutting rocks in Deep Creek is soothing and after a long day, a hot meal, and the warmth of our sleeping bags, we soon, in our respective tents, fall asleep.

Cherokee by Night

I calculate Day Two to be our toughest and longest hiking day of the trip. We have to go a total of nineteen miles to get to the town of Cherokee where we can spend the night at a local, privately-owned campground. With more than seventeen miles of wilderness hiking ahead—first along the boulder-strewn edge of Deep Creek, then climbing nearly 3,000 feet up and over Newton Bald—before descending into bustling Cherokee—our work is cut out for us.

Crossing Deep Creek in the morning, after coffee and oatmeal, requires carrying our boots along with our large packs—fording the wide stream in our sandals. Then, as much as we had hoped for an easy and level path, we discover the route crosses many mountain steams emptying into Deep Creek. In short order our boots and legs are soaked. Still, Ginger’s bell keeps ringing that she is close behind me and the hike goes on. That said, we still pause at spots where we can’t help but marvel at how beautiful the forest and creek are together and how lucky we are to be there!

Soon, the trail traverses large boulder fields which require slow and careful footing, and, so too, whether as a result of Hurricane Helene or just being an active, dynamic forest, we discover we must climb over multiple downed trees to stay on the trail.

Once again, the going is slower than I had hoped, but we both are enjoying the hike free from the steep slopes we encountered yesterday.

At one point, though, in crossing a small bridge over a larger stream emptying into the Creek, a board breaks, I stumble and fall from the bridge onto my side into the water. Suddenly being half submerge is shocking and I find myself yelling, “Fuck, fuck, fuck,” over and over as I pull my phone out of my back pocket. I had been using it as a camera, but now it is totally soaked.

I quickly throw the phone to the embankment, as I stand up and pull myself and my thirty-pound pack out of the water. Both Ginger and I search for a dry cloth in her pack and soon have wiped the outside of the phone dry. From what I can tell, the phone appears to be working and that comes with a significant sigh of relief. I don’t want to be in the wilderness without my phone even though we have no cellular service. Still, I decide to stop taking pictures and pack the phone in a plastic bag in my pack. With this incident and the storm yesterday, I realize I can’t afford to lose my phone due to the elements. In the future I will need another option for photographs—the phone is just too valuable.

Four miles into the hike we begin to ascend Newton Bald. The route rises 3,000 feet from where we are and is a new challenge for us with our packs. Yesterday we climbed down the slope, today we hike up. The route has us winding around the contours of the mountain, but always ever upward. We pass numerous bear scat on the trail, and I expect to encounter a black bear at any minute. Ginger’s bell, though, seems to have frightened any curious bears, deer, gophers, and salamanders away. We reach what we think is the top of the mountain by mid-afternoon—staying in the forest just below the crest. Unfortunately, darkening clouds and thunder in the distance presage the arrival of rain.

The descent down to the town of Cherokee at 2,000 feet in elevation in a drizzling rain takes up the rest of the afternoon and early evening. It isn’t until seven o’clock before we hike out of the forest. I am sore, my knee hurts, and my two one-liter water bottles are empty. We seriously must find a spot—hopefully our campground—to regroup.

It would have been nice to simply cross a bridge and find ourselves immediately in the town of Cherokee, but no, we are at Mingus Mills, a historic site operated by the National Park Service. We must still walk two miles along Highway US 441 to reach the town. First, though, we arrive at the Oconaluftee Visitors’ Center for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which, we discover, is closed for the evening. However, we use the picnic tables for a brief break. The bathroom facilities are still open (thank god!) and I am able to fill one of my bottles of water from the sink using a plastic cup from my pack.

It is now after eight and we’ve still a mile or more to walk in the drizzling rain to reach the town of Cherokee, let alone find our campground (free camping behind Native Brew Tap and Grill). We follow my printed directions and take the Conaluftee River Trail to town—not realizing we are on a scenic route along the river.

Now dark, I search for my headlamp to reread the directions. I am totally confused as to why we are walking a large loop near the river—thinking rather we should have reached Cherokee by now. I wish I had studied a map of Cherokee and the riverwalk so I understood our route coming off the Mountains-to-Sea Trail—a mistake that I won’t repeat in future hikes.

With my phone packed away, Ginger comes to the rescue. She pulls up her Google maps app on her phone, but instead of searching for that free campground where we would be putting up our tents on a rainy night, she finds a motel. The Great Smoky Mountains Inn is less than a twenty-minute walk away. The motel has an available room with two double beds, so we forgo the campground and wholeheartedly agree to share the cost of the motel. Soon we are in a room that is clean and perfect for drying our wet clothes, soaked shoes, and drenched backpacks.

It’s now nine o’clock and I limp into the shower. My knee hurts and vivid red rashes on both sides of my waist (due to the backpack) sting in the hot water. I must bandage these spots before hiking tomorrow. After the shower, I get into one of the beds and discover that my phone won’t charge. I am down to 14% battery life and still have two days of hiking to go. Ginger plays with it for awhile but says the phone looks like it has gotten dirt in it’s charging port—the result of falling into the stream this morning. I definitely have to do a better job protecting my phone. Another lesson learned.

Ginger heads to the bathroom to take a shower. Without meaning to, I fall asleep before she gets out. No dinner, no chitchat, no phone—just sleep after a twenty-mile hike spent with much of the afternoon and evening in the mist of drizzling rain.

Are we having fun yet? A lingering question I’m afraid to ask. I am surprised at how rusty I am turning out to be. The year away has taken its toll.

We probably should have split the day into two hikes, I decide, lying in bed the next morning—taking five days instead of four to reach Waterrock Knob. Another night along the Deep Creek would have been a relaxing respite after the day before. Still, with so much of the afternoon available to us, it would have been hard not to walk on, especially with the town of Cherokee and all of its conveniences waiting for us.

Still, getting more water from the river before attempting Newton Bald would have been smart. With all the water issues I’ve encountered on the trail in the past, I truly know better! My admonishment includes being more astute in studying the proposed route and not finding myself unprepared after-the-fact.

The Ascension

Day Three begins with aches and pain, along with motel coffee and a protein bar. Ginger’s takes an ibuprofen for her sore shoulder while the pain reliever has been a staple of my diet for the past two days. I chalk it up to age and a knee that’s worse for the wear. As it’s bright and sunny in the early morning hour upon leaving our motel room, neither Ginger or I feel like stopping to eat breakfast at a local diner. Our hike today is only eleven miles—twelve you want to count walking out of Cherokee to meet up with the Mountains-to-Sea Trail—a gift for a relaxing late afternoon after the day before. On the downside, we see from the elevational map that the walk is entirely one long ascent as we hike back into the Smoky Mountains.

Tonight we plan to camp at the Mile High Campground. “Mile High” seems a bit ominous as we start our hike in Cherokee at 2,000 feet. A mile is 5,280 feet if I recall. So, let’s be real, reaching any campground that calls itself “mile high” can’t be good.

The Mountains-to-Sea Trail leads us onto the Blue Ridge Parkway for the first eight miles. Walking on the shoulder up the road as cars, motorcycles, and pickup trucks pass by us going fifty-to-seventy miles-an-hour driving down to Cherokee is not fun, but we expect to be off this road before the day is done. The bright morning sun, intense humidity, and hard pavement take their toll in carrying our heavy packs, but the paved overlooks provide relief from the ever-climbing, endless stretch of road.

We are not permitted to hike through the two tunnels we encounter along the way, yet we enjoy being back in the forest as we cross over these ridges.

We stop at Big Witch Overlook for lunch. A cement picnic table is exactly what I need, and I am soon on my back trying to get a few minutes of a power-nap while Ginger walks around taking pictures of the vista. Another power bar, a bag of nuts, along with hiking gummies, become our lunch before we, once more, are on our way—soon leaving the Blue Ridge Parkway for a gravel road to climb the final three or four miles to the Mile High Campground.

It’s on this dirt road when things take a turn for the worse.

As we hike up the rutted road, the afternoon rains begin. We are getting use to putting rain covers over our packs and listening to thunder in the distance, but this storm is the most powerful of the downpours we have encountered. We are literally pummeled in rain and have no where to go to get out of the storm—except, that is, to reach the main office of the campground. As I walk my head down, water pouring off my hat, my nose, my arms, I envision the office having a veranda in which we can sit on wicker rockers to dry off and wait for the tempest to end, sharing cups of hot chocolate.

The height of the storm is no longer on another mountain but right over us. At one point, the blinding bright flash of lightning across the dark sky is instantaneous to the incredibly loud crack of thunder. Instinctively I crouch and start to run—but where too? There’s no where to go but follow the road up the mountain. Ginger, who is in front of me, looks like a lonely, water-logged wisp of a figure. I hear her bell, but I can’t keep up with her. I imagine telling her husband how God called her forth with a bolt of lightning. Would he believe me if I told him she immediately ascended into heaven? Saint Ginger with fried hair and a bell that exploded into a thousand pieces.

When we finally reach the campground around three in the afternoon—still in the rain—we discover it is spread across a long crest of a ridge line. The office is a small pillbox structure another quarter-of-a-mile away at a crossroads between our gravel road and a paved road coming up the mountain perpendicular to ours—that road ends at the pillbox office. The campground looks like it has seen better days back in the ‘50s or ‘60 when the office, likely, was hauled up here by tractor before mule tracks became roads. I see no covered veranda, no wicker chairs, and, stepping inside, no hot chocolate—just a small room stuffed with open boxes of supplies, assorted dirty, outdoor equipment, and a tiny desk at the far end.

An older man sits behind the desk. He says his name is David Jones. He has a white, handlebar mustache and tied-back white hair, all of which gives him a very distinguished look. He says he has a campsite for us, but he doesn’t recommend putting up our tents until the rain slows down. We totally agree and say we think the rain will stop at five. We ask if we can sit in the office. He shrugs his approval.

Ginger sits down on an old ice chest while I take a stained plastic chair. We are soaked and soon puddles of water form on the floor below us. I begin to shiver and can’t seem to stop. Ginger, too, says she is freezing. Looking at each other we know we’ve got to do something about these wet clothes. I get up and find a rack of sweatshirts and hoodies on sale next to (and almost over) David’s desk. David says the hoodies are their most popular item. I can see why and buy one. Ginger buys one too and, though we are soaked, the hoodies do their job. To stay warm, we now have Mile High Campground hoodies to add to the weight of our backpacks.

David Jones consults his computer and says the rain is now not projected to stop until seven or eight o’clock. The forecast has changed. We must get our act together, go back into the rain, and put up our tents. David, though, has another idea. He says he has an old, two-room cabin we can stay in for the night at no extra charge. It’s bare-bones, he says, but you’ll be out of the rain.

We immediately agree to take it sight unseen, so he drives us down the cabin in an old, covered, rusty golf cart that, too, has seen better days.

The first room of the tiny wood cabin is outfitted with a homemade bunk bed and the second consists of a plywood platform. A long pew from some church runs the length of the wall between the two rooms. It is insanely rustic with no windows, but it is dry and before long we have changed our of our wet clothes and are in our sleeping bags. I have the stove out and make hot coffee—so good when we have been so cold. That night we eat a rehydrated meal of Pad Thai on the church pew and before going to bed—Ginger on a bunk and me on the platform—we discuss how crazy this trip has been and how our lives have led up to this moment. I feel like I am finally beginning to know Ginger and realize how much richer, than I ever realized, her life has been.

Still, in truth, the hardships Ginger has gone through these past three days may keep her away from ever thru-hiking again. I understand but am sad about this too. I wish I had been more of a mentor in promoting this experience. I’m just not, I realize, on top of my game enough to make this hike anything more than a series of hardships.

As night closes in, we realize to our dismay the bathhouse with showers and toilets are a half-mile away, so we pee off the front porch—Ginger more discretely than me.

Junior Rangers

We wake up early on Day Four and are excited to get going. Our final day. Coffee and a power bar start our morning, once again, as we walk up to the bathhouse for more water and a bathroom break. Seven miles to reach the top of Waterrock Knob—how hard can this be? It turns out, a little more than we bargained for…

The hike begins by following the perpendicular road down hill into a valley or saddle—not a good sign when we have to climb to 6,300 feet to reach the top of Waterrock Knob. Three miles in, we’ve crossed the small valley and begin in earnest to hike up the mountain. The going is slow but steady. Halfway, we notice the route becoming more and more rocky. Soon, with two miles to go, we are hiking an ever-upward trail over endless rocks, with large boulders added to keep us light on our toes.

Scrambling over these boulders on a steep hillside make for a cautious but steady climb—especially given my knee restricted in the tight brace. With three days of hiking already under our belts, there is nothing to be done about the knee—it will need to be evaluated, once more, when I get home. The sound of thunder in the distance, though, keeps us focused on staying in the moment and moving ahead.

As we climb higher, the number of boulders increase and create large formations of vertical rocks stacked against and on top of each other. This, then, is our trial for the day. Just when we thought that finally we would have an easy time of it, the Universe says otherwise. With one last all out effort of strength and sweat, we scramble over one rock formation after another and finally, finally make it to the top.

A bench recognizing a leader in the Carolina Mountain Club proves hard to resist and we take off our packs, sit, and enjoy the panoramic view of the surrounding valleys. We are a quarter-mile from the end of our hike. As we enjoy the moment, we spot a couple walking towards us. They, too, seem to be enjoying their time on Waterrock Knob. We greet them but warn them, too, about the trail we have just climbed. After a lingering peak, they turn and quickly go back the way they came.

Shortly thereafter, Ginger and I come full circle—completing the trail much like we started it, walking in a crowd of tourists to the parking lot and visitors center.

We call Kathy, my cousin David’s wife, who agrees to drive the hour to Waterrock and pick us up. (Thank you, Kathy, thank you!) As we wait for her, we sit on a curb and lean against the white side of the visitors center. A group of newly appointed Junior Rangers walk by who are between eight and thirteen years of age. If, indeed, they represent the start of experiencing nature in the wild, perhaps, then, we are at the end of such a lifelong enjoyment. We congratulate them on their accomplishment, but they just stare at us in awe: two sweaty backpackers who have come out of the dark forest and are now incongruently sitting in their bright, secure world.

Yes, that’s exactly who we are: two sweaty backpackers. And yes, that’s me. I am a thru-hiker, once again—flaws, mishaps, and all. It’s been this way across North Carolina, and I am here now at the end of another segment, totally at peace with it. Totally at peace with who I am. One thing I am not—I am not a victim of cancer. I am not someone simply going through the medical motions of staying alive.

I note, too, Ginger looks happy and seems to revel in her accomplishment. Perhaps there will be more to our story than I realize.

That night we sleep near the top of my cousin David’s mountain and take pictures of the glorious sunset. Once again, it rained in the mid-afternoon, but this time we were taking showers and changing into the clean clothes we had stored in the car. Ginger doesn’t jump at my invitation to hike Segment Two, at least not yet, and I really do need to heal my knee before I go back out—but, in the limited time I have remaining—I give it six weeks, six weeks come hell or high water…

Ginger and I both agree, this segment, Segment One, which starts the Mountains-to-Sea Trail on its path ever-onward to the Outer Banks, turned into one incredible adventure. It’s been an unique adventure as well. Totally unique, like so many of the other segments I’ve experienced walking across this long state. With two segments to go in the Great Smoky Mountains, I can’t help but wonder what I’ll encounter—what adventure in which I’ll find myself—tackling the miles ahead.

The mountains-to-Sea Trail. This chapter focuses on Segment 1B as I flip flop my hike. With the impact of Hurricane Helene on Segments Three and parts of Four, my goal is to tackle Segments One and Two and most of Four this summer.

Just about my favorite part is the chronicle of all the obstacles you face. That sounds wrong since your health is such a big obstacle. But I did love the story of your determination and all the things that went wrong -- dirt in the charging port! Really good.

Where does the drive to experience life on the trail come from and where does it go? You clearly have a gift for finding and keeping that drive going. I can not imagine making that hike although the Great Smokies are one of my most favorite spots I’ve ever been to. I certainly admire your spirit and determination and enjoy those pics you are lucky enough to see first hand. The rain, lightning, and thunder would have me curled up in a ball at the bottom of the mountain! Onward you go! I hope the weather gets better for the next section! Thanks for sharing your journey.

PS. Do you really have a friend named William Blake? 😙