Betwixt and Between

MST. Chapter 40

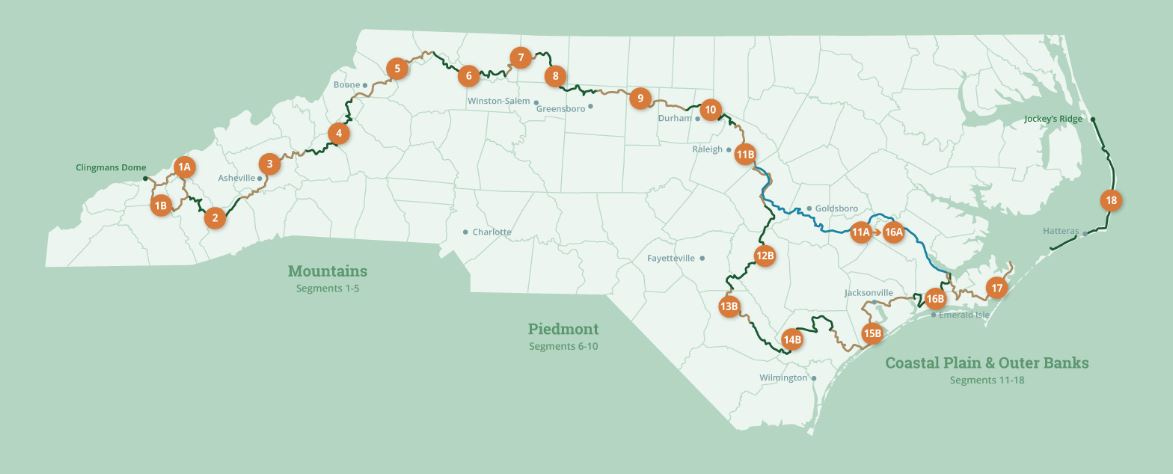

This is my serialized story of hiking the Mountains-to-Sea Trail (MST), a 1,175-mile route that crosses the state of North Carolina. I’m hiking west from Jockey’s Ridge near Nags Head on the Outer Banks of the Atlantic Ocean to Kuwohi (formerly Clingmans Dome) near the Tennessee border in the Great Smoky Mountains. If you’d like to start at the beginning of my story, click here.

See the Mountains-to-Sea map at the bottom for reference.

This whole situation is killing me. I’ve got to make a decision and the paths ahead are totally undesirable. How could it come to this without me knowing which way to go?

Listen, I’m just an ordinary guy trying to avoid the tree falls and slippery slopes of life’s many passages. At no point have I venture into unknown territory without a cell phone, map, guide, or hiking app to show me the way. Why on earth would I go forward so blindly now?

Let’s be real. I’m talking about prostate cancer and my treatment options.

I can’t even figure out how I got prostate cancer. If it’s genetic, like some doctors say it might be, I am happy to report that my two brothers, so far, are cancer free. One, Charlie, is three years older than me and my other brother, Jeremiah, is six years younger. Given our ages, all three of us are essentially old men and all of us should be extremely susceptible to prostate cancer, Yet, thank goodness, I am the only one of the three of us with this diagnoses.

Perhaps, just like my thirty-pound pack, this is simply my burden to carry. Charlie recently had knee replacement surgery and doesn’t need this on top of that to slow his recovery, and Jeremiah with a young wife and now being the proud father of three girls under the age of ten, has much on his plate too and can’t afford a bout of cancer to add to his life.

This situation, then, is all good. I pray the cancer is not in my family’s genes and stays confined to me.

Maybe, rather then, the cause is more environmental. Still, this would be strange. My house is in a modest suburban neighborhood with no coal-burning factories and no agricultural fields sprayed with insecticides in the nearby area. And, for that matter, at no time have I ever lived around such cancer-inducing locales.

In general, my cul de sac life would be rather boring if it wasn’t for the thru-hikes I’ve undertaken over the last few years and the new ones I still envision.

Given my health, I can’t help but think I’m the last person who should be diagnosed with this cancer. I’m in my eighth year of being vegan and for the most part have stuck with a whole-food, plant-based diet of unprocessed foods. I haven’t eaten meat during that period, except on rare occasions, such as when nothing else was available in hiking the Camino de Santiago in Spain, or while on the Mountains-to-Sea Trail.

Instead, what I have done on the Camino and on the Mountains-to-Sea Trail is snack on bags of potato chips, Snicker bars, and orange sodas. But, really, can this be what sparked my latent cancer cells out of their dormancy? Is this why these mutated cells are now killing me? Really?

Someone, then, needs to put a caution banner on the Mountains-to-Sea Trail website that says potato chips, Snickers bars, and orange soda might be detrimental to your health. Yes, the staff has managed to clear tree falls, dig across mud slides, and build bridges over rivers, but watch out for those pesky convenience stores.

It’s not like I have been a slouch—like cancer comes to couch potatoes. Given my desire to get stronger after the Camino, I have been exercising at my workout gym on a daily basis for nearly two-and-a-half years, reaching my goal of two hundred-and-fifty camps this year…

…while, at the same time, hiking across the state on the Mountains-to-Sea Trail.

So, in another words—what the hell is going on?

A friend from high school who has prostate cancer himself and has made similar lifestyle choices, says the only thing he can think of as to why he got cancer is “being an old man.” Damn! How do you fight being an old man? One statistic says that one in three men will get prostate cancer in their lifetime.

Who knew? I was fully engaged in my goal of hiking the Mountains-to-Sea Trail and simply had my annual physical between Segment Five and Segment Four last summer. When the results came back, all hell broke loose.

The question at this point, though, is not how I got it, but how bad is it?

This answer arrived in mid-January with a PET scan at the Duke University Cancer Center. This process entailed being injected through an IV with some special radioactive-type solution that probably could kill rats. I was directed to lie down in a round chamber where hundreds of x-rays were taken of me from neck to knees. Luckily, I had been reading a book called Breath by James Nestor and used my time to practice breathing through my nose, which, by the way, the author argues is a lost art given our propensity for mouth-breathing.

The next day—thank god—in addition to being super relaxed due to practicing nose-breathing by taping my mouth shut all night, the results of the PET scan showed no sign that the cancer had spread beyond the walls of my prostate. Woohoo!

Given my initial PSA tests were so damn high—as was the Gleason score from my biopsy in December—I realize I must come to grips with a treatment plan.

The Duke oncology surgeon is a Marcus Welby-type character right out of that old TV show. A day after my PET scan he studies my biopsy. He says that typically men my age are steered to radiation and hormone therapy, but due to my overall health, he recommends I go ahead with surgery to remove my prostate. He says, I could be back exercising in six to eight weeks and hiking in three or four months. And, with surgery, he adds, I likely will live another twenty to twenty-five years. Hmmm…

If only I can get over the shock of the initial recovery process, including a catheter up my penis for two weeks (to drain my urine), and, then, wearing diapers and pads to handle my incontinence those first few months while I trained my pelvic floor muscles to do what my prostate did naturally for seventy years.

Shortly thereafter, my wife Karen and I meet with the radiation oncologist as well as the clinician who oversees hormone therapy. The radiation oncologist, a brisk man in surgical scrubs, quickly runs over the situation. The radiation would be limited to twenty-eight sessions over the course of five-and-a-half weeks. However, given my test results, a hormone therapy treatment of 24 months would be required.

The clinician, a thin, mild-mannered man in his early forties says that the hormone treatment is designed over the next two-year period to kill the testosterone on which prostate cancer cells feed. My testosterone. The side effects, he cautions, are not experienced by everyone, but can be significant: muscle loss, fragile bones, weight gain, hot flashes, tiredness, erratic behavior, etc., etc. With each pronouncement, I feel like I am losing the essential pieces of who I am, AND after the twenty-four months of treatment, I will turn like a wilted hulk into what I dread the most: a withered prune of an old man.

In truth, I can’t help but think if I get hormone treatment I will never complete the Mountains-to-Sea Trail, let alone any other long-distance trails.

Of course, I could do nothing at all regarding my cancer, I suppose. Many men live normal lives and die of other causes way before the cancer kills them. I could fall off of a cliff in the Great Smoky Mountains, I could drown in a raging river, I could be bitten by a Brown Recluse Spider or a Timber Rattle Snake, heck, I could even be attacked by a Black Bear. Still, I bet, for those who succumb to such fates, their cancer levels were much smaller than mine. In fact, I feel terribly lucky the cancer cells have not extended beyond the prostate. I’ve got to do something.

By chance, on Thursday, later that week I am at the administrative offices of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail in Raleigh, North Carolina. When I arrive, Betsy Brown, the associate director, is excited to show me the many maps on her desk. She and Brent Laurenz, the executive director, have just returned from meetings with the U.S. Forest Service in Western North Carolina.

Betsy, in blue jeans and plaid shirt with her thick white hair pulled back, says that she and Brent were told by the Forest Service that many parts of the trail through the Pisgah National Forest may open as early as this spring.

This is thrilling news as I had to stop just before undertaking a five-day hike through the Pisgah National Forest. Hurricane Helene decimated this entire segment of the MST. Betsy, though, is thrilled and saying, “Jonathan, soon you will be able to compete the trail. Isn’t that great!” She’s pointing, all the while, to red lines on her trail maps that will be opening. She powers up her laptop to show me what this means in terms of the big picture. Damn! This is doable.

Though some spots near Segment Three of the MST will take years to open, Betsy is telling me I could skip them before continuing westward in my final push to reach Kuwohi, formerly Clingman’s Dome, in the Great Smoky Mountains. Kuwohi is the official end-point of this 1,175 mile journey. The only problem is my fucking prostate.

I tell Betsy of my dilemma, and she says, “Don’t worry about this spring. The more time you take over the next few weeks, the more likely the trail will be restored.”

I tell her, “If I can get onto the trail by late summer or early fall, I might be able to finish it this year.” She nods her head with a big smile. “That’s right. Even with your setback, you might be able to complete it before the year is out.”

For me, urgency is the issue. Men my age don’t have that many thru-hikes in them—can I handle twenty-four months of hormone treatment before I start up again? And what if the cancer returns two or three years later. I read cancer cells from the prostate have a 35% chance of reoccurrence somewhere else in the body. I’ve also read that prostate cancer cells become more tolerant of radiation.

That Friday night I get a call from Doug Veasey. He’s the trail manager for Segment Four, the segment where I stopped.

He tells me he just met with Betsy and Brent with the U.S. Forest Service.

“Betsy and Brent said I should check your blog, so I’ve read your most recent posts. Thank god your wife stopped you from hiking the week of Hurricane Helene. No one could have survived that.”

“But,” he adds with a laugh, “tell your wife, if you decide to take on the challenge of completing the trail this fall, my crew and I will make sure you complete it.”

The next morning at the Burn gym, I tell Ginger, who hiked with me through the Grandfather Mountain area of Western North Carolina, about my conversation with Doug, what Betsy said earlier, and all of Betsy’s maps of the trail’s reopening.

Ginger responds by telling me if I go ahead, she’ll take the week off from work and hike with me through the Pisgah National Forest.

I say, “I definitely can recover from the surgery by this fall.” That’s it then. Surgery.

To get back to normal as quickly as I can. To have some additional treatment options for the future.

AND, come hell or high water, to complete the final four segments of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail this year.

Jonathan,

There are many options to treat prostate cancer; deciding which one is often the hardest part. It sounds like you made the right one for you. I have no doubt that you will complete your MST quest. We don't call you the Camino Beast for nothing. 💕 Marlene

Walk 🚶♀️ 🚶♂️ on brorher walk 🚶♂️ 🚶♀️ on!